learning & unlearning

learn about ecological gardening and how it positively impacts the earth and unlearn the aspects of conventional gardening that negatively impact the earth

topics covered:

- Permaculture

- The Conventional American Lawn

- The Soil Food Web

- The Importance of Native Species

- The Importance of Soil

- Sustainable Agriculture vs Conventional Agriculture

- Extreme Heat, Drought, and Flooding

- Things I Do That Don’t Cost Anything

- Bigger Steps I’ve Taken

- Books & Films Where I Got Info

- A Very Important Note

My favorite description of ecological gardening comes from the book that sparked my passion for it and inspired me to create my own garden with no turning back, a quote as beautiful and eloquent as the natural processes themselves:

“...at the heart of the ecological garden, we are not mimicking the form of nature. We are cultivating the conditions for natural processes to occur, so that our landscapes behave like ecosystems and tie into the rest of the harmonious relationships that knit this planet together.”

Toby Hemenway, Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture 2009

Permaculture

Permaculture is a design approach used to create sustainable human settlements. A contraction of permanent culture and permanent agriculture, it was developed by Australian Bill Mollison in 1959 and expanded upon by his student, David Holmgren, based on observations in nature and indigenous people. I use many permaculture principles in my ecological garden, but permaculture is much more expansive than that:

“If we think of practices like organic gardening, recycling, natural building, renewable energy, and even consensus decision-making and social-justice efforts as tools for sustainability, then permaculture is the toolbox that helps us organize and decide when and how to use those tools...It, like nature, uses and melds the best features of whatever is available to it."

Toby Hemenway, Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture 2009

The Conventional American Lawn

Boxwood bushes lined up against the house, a couple of sago palms and knock-out rosebushes dotting the flowerbed, dyed mulch, perhaps a crape myrtle, the rest of the yard filled with St. Augustine grass. Mow it or have someone scalp it at least every two weeks, whether it needs it or not, with noisy and noxious gas-powered lawn equipment. This is the prized Houston yard. So why is this conventional type of landscape so bad?

Well, essentially it’s a sterile environment that provides nothing but a passed-down notion of beauty and status that is extremely wasteful and a constant struggle to maintain. (Not to mention the air and noise pollution caused by gas-powered lawn equipment.) Native trees, shrubs, grasses, and flowers are adapted to our regional conditions, and once established, require very little in the way of supplemental watering and fertilizer. Non-natives, on the other hand, require excessive amounts of water and fertilizer to survive. Non-natives provide more limited and sometimes no benefits to our wildlife, including birds, butterflies, and insects.

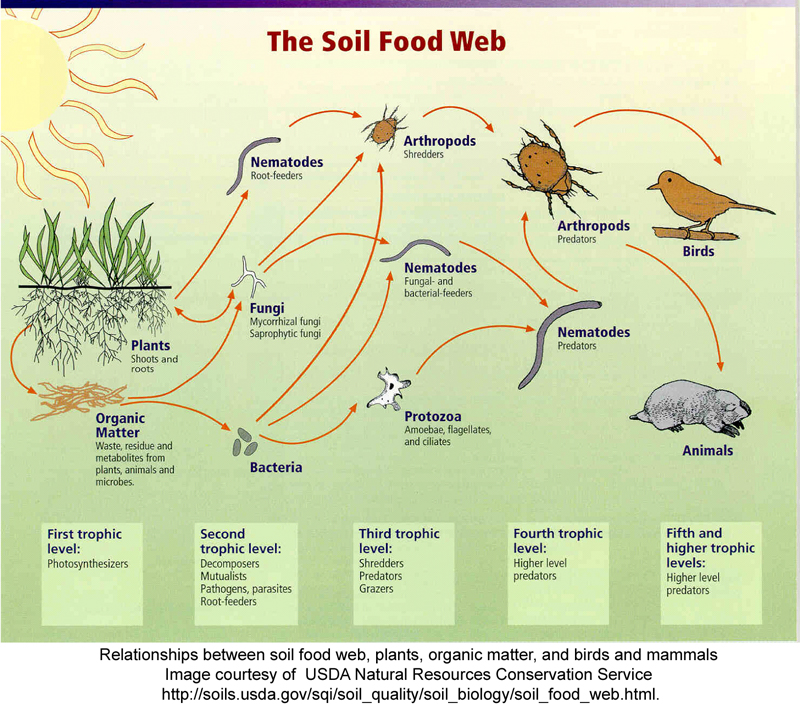

Now, you may think it’s a good thing, not to provide any benefit to insects because you don’t like them or don’t want them in your yard, but you may want to reconsider that position. The fact is that we need insects to survive. They are an essential part of the Soil Food Web and essential pollinators. That is why we don’t want to recklessly spray pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides to solve our yard problems–in doing so we are killing what is giving the soil fertility and health, as well as poisoning the pollinators that pollinate our plants and, thus, the food sources that other wildlife, and we, if food gardening, consume. The good thing is, if we create an ecological garden, the pests and the disease are largely kept under control by that very system. We also need microorganisms in the soil to keep it healthy. It’s all part of the Soil Food Web. The very much alive, invisible world in healthy soil, the micoorganisms–archaea, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, protozoa–to the earthworms, slugs, snails, pill bugs, centipedes, millipedes, and spiders we can see–to the arthropods: flies, beetles, springtails, ants, dragonflies, damselflies, lacewings, moths, butterflies, bees, wasps–to the amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Then, of course, the plants. All of these are essential to a functioning Soil Food Web.

“If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.”

E.O. Wilson

The Importance of Native Species

I’m a big proponent of planting native species and avoiding invasive non-natives. As I previously said, they are adapted to your regional conditions, thus, requiring less resources. Now, there are non-natives that do well in our gardens because their origin has similar conditions to ours. However, here’s the biggest problem: our insects cannot eat them. Our native insects have evolved alongside our native plant species for thousands of years–it’s not something they can evolve in decades. And without these insects, our birds don’t have a food source to feed their young, and other insect-eating wildlife such as lizards, frogs, toads, and bats lose their food source. (Native hybrids could potentially be a problem for native insects, for example, if the size of the bloom is different from the native, whereby they can’t access the nectar.) Butterflies can definitely drink the nectar of many non-natives; however, they can’t use the non-native as a larvae host. Birds typically don’t nest in non-natives. While having some non-natives is not bad, permaculture strives to increase the number of functions each element in the landscape provides, and natives have that multifunctionalism. And of course, any food garden in Houston is going to be non-native. Otherwise, the only thing we’d be eating would be pecans, persimmon, Mexican plums, elderberries, dewberries, muscadine grapes, tiny wild tomatoes, and various greens we typically consider weeds.

Note: when I use the term native, I am referring to plants and animals native to my fairly specific region: Houston, Harris County, Southeast Texas. A Texas native is not necessarily going to do well in my region, as east, west, north, south, and central are all vastly different from each other.

The Importance of Soil

Healthy soil is fertile soil, alive with beneficial microorganisms. It is a sponge for rainwater and carbon dioxide, a reservoir of nutrients for plants. Unhealthy soil is sterile; it releases water and carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere and leads to desertification of the soil.

In order to build healthy soil, we need lots of organic matter. This is one of the first things I implemented in transitioning my backyard from a conventional landscape to an ecological garden, along with setting up a rain barrel to harvest rain water and composting kitchen scraps. Two free sources of organic matter may already exist in your own backyard: fallen leaves and grass clippings. I no longer call it leaf litter or yard waste. It is not. It is a free source of stored nutrients that protect and replenish the soil. So why do we would spend so much time and energy bagging them up to be taken away? I’m trying to create as close to a closed, self-sustaining system, as possible.

There’s an old gardening saying that I adhere to: don’t put a $5 plant in a 50 cent hole. Meaning, the soil is more important to the success of a plant. This is one area where you don’t want to skimp. For my fruits and vegetables, I invest in raised beds–necessary in Houston–and purchase high quality organic soil. (If you have the patience, you could create your own soil through composting, but I only do this for my non-edible plants.) I also bring in high quality native wood mulch, compost, Microlife 6-2-4 Fertilizer, and Microlife 4-2-3 Ocean Harvest. I don’t use any synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides. I haven’t had to.

Natures tries its hardest to have no bare soil. That’s why we have the dreaded weeds. Weeds are basically pioneer species that thrive in very poor conditions, that come in to cover the bare ground until succession of other species occurs. It’s nature’s intelligent way of protecting its bare ground. I cover my bare ground with either compost, mulch, or fallen leaves in the bare areas depending on my future plans for them. If I want to encourage groundcover, I will put down compost. If I am waiting for my native plants to get bigger, I put down mulch. If I simply want to cover a path, I put down fallen leaves. Basically, these three materials can be thought of organic matter in different stages of decomposition, so compost is the most decomposed, meaning its nutrients are most readily available–making it more expensive–while high quality mulch is less decomposed and backyard leaf litter is the least decomposed, meaning it needs to break down further until its nutrients become available. All of these help the ground retain moisture–thus helping mitigate flooding–block out weeds, feed the soil and the soil’s microorganisms, and draw down carbon.

In fact, according to the documentary Kiss the Ground for every 1% increase in organic matter, one acre of soil draws down ten more tons of carbon! If we transformed our conventional, industrial farms into multi-faceted pastoral landscapes that farms once were and utilized regenerative and permaculture farming techniques, we could help save ourselves from the environmental disasters increasingly befalling us.

Modern agriculture has pumped 70% of the soil’s carbon into the atmosphere. Our legacy load, which went up drastically from the start of the Industrial Revolution is 1,000 gigatons. This is the amount of carbon that would still be there even if we ceased all emissions. However the soil has the potential to hold more carbon than all the plants (1,100 gigatons) and the atmosphere (600 gigatons) combined. The soil has the ability to hold more than 4,000 gigatons of carbon! We could sequester 6 gigatons of carbon a year by switching conventional farming to regenerative farming. This would compensate for the 4.3 gigatons per year we are currently producing and make a dent in our legacy load! [Kiss the Ground]

Now, I totally understand that even if every single person converts their yard to an ecological garden, it will not make a dent in total greenhouse gas emissions. But teaching this and putting it into practice can further the larger consciousness and mindset of the general public. It is doing on a smaller scale what needs to be done on a larger scale, and, still, that is only one piece of the pie. The real change must be taken in policy and industry. But it’s something. And every bit of food that we can produce ourself means it’s not coming from industrial agriculture.

“...in nature nothing exists alone.”

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, 1962

Sustainable Agriculture vs Conventional Agriculture

Sustainable agriculture is kind of like the ecological garden on a larger scale. The principles are similar. Though all have their differences, permaculture, regenerative agriculture/farming, holistic management, rewilding, are all along the same lines. Conventional or industrial agriculture is the direct opposite. Our yards, again, can be seen as smaller versions of the same thing.

Sustainable Agriculture

- harnesses the cycles of nature

- closed system, nothing wasted

- polyculture (diverse plants & animals)

- small-scale and local

- limited inputs–soil food web provides its own fertility, pest management and sanitation

- utilizers cover crops, no-till methods, and rotational grazing of animals for soil fertility

Conventional Agriculture

- tries to control nature (unsuccessfully)

- exceedingly wasteful

- monoculture (one crop, one animal)

- industrial food chain

- relies on tons of expensive inputs (synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides)

- tilling depletes the soil of nutrients long-term and bare soil during the off-season furthers soil erosion and desertification

“So long as never-ending economic growth remains the goal of our governments and our major financial institutions, and so long as the corporate bottom line continues to put immediate profit above the future of our children, and so long as so many of the world's inhabitants continue to live in unalleviated poverty, the crimes of the natural world will continue.”

Jane Goodall, Seeds of Hope, 2014

Extreme Heat, Drought, and Flooding

Houston is definitely experiencing more and more extreme heat, drought, and flooding, as are many parts of the world. It pains me when my two 55 gallon rain barrels are overflowing with rain water during a storm, only to be used up in the next two weeks, when the heat wave and drought hits. In anticipation of another hot, dry summer, I installed a 50% shade cloth over my raised bed and grow bags that bear the brunt of the direct overhead sun. It reduced the temperature by 20 degrees! It also helps to keep the inside of that part of the house slightly cooler. The many trees around the house also go such a long way of keeping the yard from desiccation, though the existing St. Augustine grass and native basket grass are finally becoming crunchy after this summer’s second drought/heatwave of 100+ days. If these trees were not here, I would be in a mad rush to plants as many trees in my yard as I could.

I hadn’t know this, but 60% of our rainfall comes from the oceans, called the large water cycle, while 40% of our rainfall comes from trees and plants, called the small water cycle. Without trees in vast swathes of land covered by desertification, monoculture farming, concentrated animal feeding operations, and concrete, we experience more and more drought, flooding, and heat waves. [Kiss the Ground]

I also hadn’t know that at 86° F photosynthesis stops or slows significantly for most plants. At 90-95° F pollination decreases in most plants and sugars are reduced. At 104-113° F the enzyme proteins of most plants cannot function properly. And at 122° F virtually all proteins are altered and the plant dies.

Things I Do That Don't Cost Anything

- Use what I already have: the most sustainable item is the one you already own

- Consume less–of everything

- Evaluate what I bring into my home

- Question the way that I do everything–is there a better way?

- Live more seasonally and local (eg. cook with food that is in season)

- Create as close to a closed system as possible–not wasting anything

- Giving away or recycling what I have no use for

- Don’t use poisons (pesticides, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, synthetic fertilizers, etc)

- Don’t use/limit gas-powered lawn equipment (mowers, weed-eaters, leaf blowers)

Bigger Steps I've Taken

- Investing in rain barrels, a push lawnmower, electric weed-eater and leaf blower

- Composting kitchen waste and yard materials

- Improving our soil

- Growing some of our own food

- If I do need to buy:

- –buy local, if possible

- –buy things that will last

- –buy used, if possible

- –buy from folks who follow the same ethical and sustainable guidelines, like co-ops and community-supported agriculture (CSA’s)

Books & Films Where I Got Info

- Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture, Toby Hemenway, 2009.

- The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, Michael Pollan, 2006.

- Kiss the Ground Documentary (Netflix) 2020.

- Year-Round Food Gardening For Houston and Southeast Texas, Bob Randall, 2019.

A Very Important Note

Ecological gardening and permaculture and all of these ways of stewarding the land are not new concepts. They were and are practiced by Indigenous People all over the world.